How Quickly Can We Get to Critical Mass?

Critical mass is the minimal number of atoms an atom bomb must disrupt in order to trigger a chain of fission reactions resulting in a massive explosion. We are trying to create just the right cultural catalyst to trigger a viral response from the community. We need advocates who are so passionate that the audience will generate on its own so long as we keep providing the platform. And as anyone who has survived this recent pandemic knows, virality can be measured.

If you want to grow without paid marketing, you need a viral coefficient of 1.0 or greater. That means for every customer that learns of you they tell at least one other person about you, your product, or service. If one out of ten customers shares your service with someone else, then you have a viral coefficient of 10% or point one. If one tells two people then that is a viral coefficient of 2.0.

The Problem of Distribution

There is a common misconception that if you make your product good enough it will sell itself. But this simply is not the case. Obviously if no one knows about your product they’ll never know how good it is. Now it is possible on a social network to get lucky and trigger algorithms if you have a really novel and shareable idea that fits your initial audience, but again, it requires some luck and a highly shareable unique idea. The problem is that the quality of your product, and your access to distribution channels are two entirely separate issues that each need to be solved independently. You need both, a good product, and access to distribution channels. This is such a common problem that it has been articulated in the following cliche,

“1st Time Founders Focus on Product. 2nd Time Founders Focus on Distribution”

This is not discussed as much in the Lean Startup, but I think it is yet one more assumption we need to test with our value proposition hypothesis. Can we even get access to our audience and can we capture their attention once we do?

According to Malcolm Gladwell’s book titled, “the Tipping Point,” we need to reach the gatekeepers of big media outlets, the mavens who are experts in our niche, or the few people who are really well connected to larger networks. These people already have their own audience and have established trust among their viewers.

They might not be as hard to reach as you might think. If they are publishing content on a regular basis then are probably constantly on the lookout for something new to share with their audience. So if you provide something new for them to share as content, it is worthwhile for them to give you access to their audience in return for something new to get hyped about. Just make sure you have a clear simple way to express how great your idea is.

Paid Marketing

Paid advertising like using Google or Facebook ads is a little harder to calculate, but in general we can estimate that somewhere between .2 and .5%, of those you pay to show your ads to, will click on your ad. Showing ads to older people who tend to spend more cost more to advertise to, perhaps as much as $3 for every click through for a specific niche. And young people, who typically spend less money on the internet, also cost less to advertise to–perhaps only $1 for each click through, in a very specific niche or unique key word search. So there is a lot of variability, but luckily these two variables kind of cancel each other out. Older people are more expensive to advertise to but are also more likely to make a purchase. These are extremely rough estimates, but there is a lot of data available allowing us to come up with back of the envelope math that includes a wide range of possibilities.

Depending on what you have to offer we could make another estimate that somewhere between 1 or 2 out of every 10 customers who click on your ad will buy your product if it costs around $20. Ultimately that means that to cover the costs of your marketing campaign, you need each purchase to cover the advertising costs of somewhere between $20 to $30. So for a product that costs as little as $20 you would hypothetically need to at least double the price, or eat the costs operating at a loss until you can get to the point where you have free word-of-mouth marketing. That is a really high initial cost.

LTV Life Time Value

It would only be worth investing in marketing if your customers are going to be returning customers making multiple purchases, or pay a recurring subscription fee. If that’s the case, then even if they stop subscribing after a year they would have a life time value of $240 if they pay $20 a month for that first year. This measure is also known by its abbreviation LTV. A contributor who makes a $2 donation every month for 3 years for example would have a lifetime value of $72. If it costs you $10 to $30 to show your ad to reach that customer, then your $72 of revenue would immediately be reduced to anywhere from $32 to $62. This is not profit because you still need to pay for all the other costs involved with running an operation. And again, covering the costs of advertising may already have reduced your profits by as much as half.

Word of Mouth Marketing Is Free

So as you can see, it’s quite difficult just to break even without some degree of word of mouth marketing. Advertising could help kickstart a great idea, but could be a heavy burden on your operations costs for a mediocre one. Even if we speak strictly from an accounting point of view, pleasing your audience to the point that they advocate for you is critical to success. The degree to which they do your marketing for you will ease most of your burdens, and the degree to which you fail to match their needs, the more you will struggle to meet your own.

Prioritize Work That Changes Customer Behavior

Almost no startup is profitable from the beginning. And most startups fail, either because they run out of resources or because the team gives up before they can really catch on. But contrary to common thought, startups don’t starve, they drown. They drown in doing too much work. Adding too many features. Like I said before, programmers love to program, engineers love to build, and artists love to do art. They’re ideal workplace is one where they can put their heads down and work forever without ever being bothered. Any kind of management can feel like an incursion to getting real production done. But the problem is that you will never stop running out of new ideas on how to hypothetically improve the product and the product will never be as good as you imagine it could be if you just did a little more. This kind of perfection will kill your chances of ever knowing if anyone really cares.

We must validate whether our work is actually changing customer behavior. Will this improvement increase the number of customers? Will it inspire our current customers to share it with others? If not then perhaps implementing that idea at this stage would be an utter and total waste of resources. You can easily drown yourself in work. But if you want to survive you must restrict what you work on to work that really matters.

To do this we must continuously and mercilessly rank order our task lists. Prioritize the tasks that will affect the majority of users and most change their behavior. And we must remove from our task list all but only the most essential work. To know which work is critical, it must be measured. You cannot improve what you cannot measure. This process is called validation. Any tasks that cannot be validated should probably be eliminated from your to-do list altogether. Let’s mercilessly cut down on our work, so that we can free ourselves up to think about what really matters–learning from the feedback given by real customer interactions.

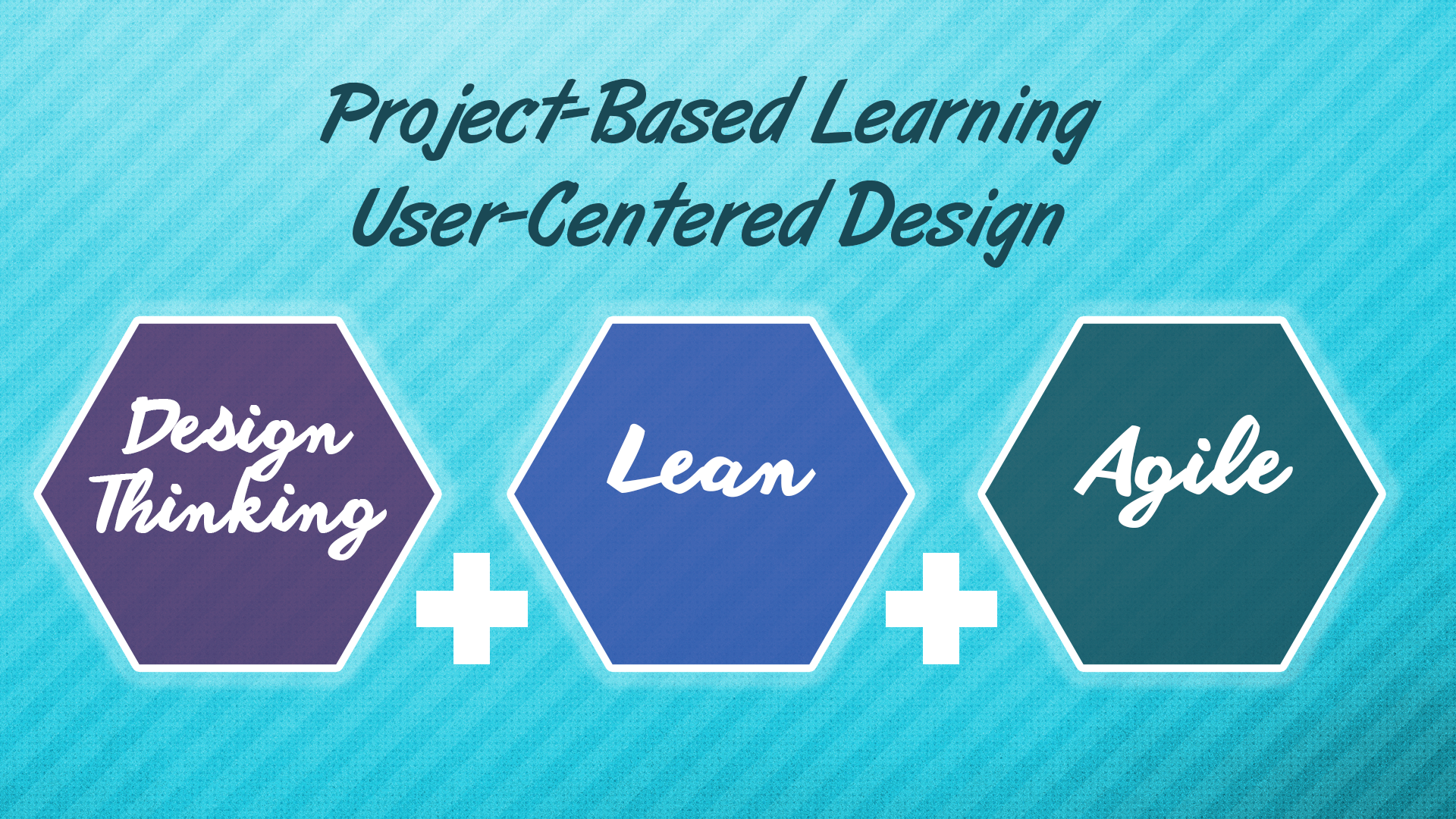

Agile

This process of deciding what tasks we will and will not work on, and then doing that work as quickly as possible so that we can deliver a prototype to real users, has a whole framework of its own, which we call the Agile Process, or more specifically, SCRUM.

For me personally, it’s my favorite part of this series, because it deals with productivity and learning these techniques greatly improved my own personal efficiency. I especially love the use of Kanban boards, a simple method that visualizes your work and allows teams to collaborate in a way originally inspired by the Japanese. So in the next and final part of the series we will learn how to use Agile to build the right thing, build it the right way, and find out the difference as quickly as possible.

There’s much more the book, the Lean Startup. It is one of the rare books where every chapter is dense with useful frameworks and useful ways of thinking, unlike most books that have maybe one or two good ideas. And for an even more detailed step by step guide I would recommend the version from MIT called, “Disciplined Entrepreneurship.” It gives you much more detailed analysis of how to do market research and very linear strategies you can follow if you are serious about building a business around something truly new.

For links to these books, and visualizations to help you get you more deeply understand these concepts, or to listen to the rest of this series on startup methodologies, be sure to visit our website at www.BestClassEver.org.